The First Film to Use Intertitles Was Also the First Dickens Adaptation

Note: This is the fourteenth in a series of historical/critical essays examining the best in film from each year. Essentially, I am watching films from the beginning of cinematic history that interest me and/or hold some critical or cultural impact. My personal, living list of favorites is being created at Mubi, showcasing five films per year. All this being explained, what follows is an examination of my fourth favorite 1901 film, SCROOGE, OR, MARLEY’S GHOST, directed by Walter R. Booth.

There are many reasons why Charles Dickens’ work has remained timeless, reasons that I won’t really go into here. Much has been said about his prose, characterization, and social commentary, and many film and television adaptations of his greatest works have received similar attention for their ability to transmit these traits to the screen. SCROOGE, OR, MARLEY’S GHOST doesn’t really belong among those conversations, but nevertheless, it does hold value as a brief novelty.

Directed by Walter R. Booth and produced by Robert W. Paul, SCROOGE, OR, MARLEY’S GHOST is the first full Dickens adaptation; THE DEATH OF POOR JOE was based on a character from Bleak House and released earlier in 1901. It also holds the distinction of being the first film to use intertitles. Both firsts hold some caveats, brought about by the natural limitations of the medium of the time, but they alone can hold some attention for the film’s abridged run time.

The film was originally about six minutes long, but the only surviving footage is just shy of three and a half minutes. The surviving cut rushes the plot by at a breakneck pace, but it’s clear that the full six minutes wouldn’t have somehow magically delivered the nuance of the original novel. The movie also makes an interesting change of story, likely inspired by the 1901 stage adaptation, Scrooge, by J.C. Buckstone.

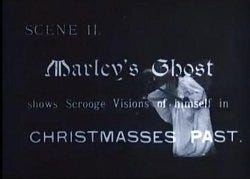

Instead of being educated by the novel’s three ghosts (of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come), Scrooge is shown the error of his ways by his deceased partner Jacob Marley. Marley’s expanded role simplifies the story, yes, but I can understand Buckstone’s original decision being made to solidify the importance of the message being communicated to Scrooge; it comes from his dead “friend,” rather than ambiguous ghosts unfamiliar to him.

That being said, this element of the creative decision doesn’t necessarily come through in SCROOGE. The shortened version we have today doesn’t help matters, but it does ironically provide another wrinkle. The film begins and progresses in alignment with the original story, but ends as Scrooge is shown the happiness of the Cratchit home, then sees the Christmas Yet to Come and the death of both himself and Tiny Tim. The film just ends with the death of the poor little Cratchit boy. It’s such a dark reading of the Christmas Carol story, for no other reason than film preservation, but it ends up being what comes through. That alone sets the mood of SCROOGE apart from other adaptations of the tale, even if it was never intended.

The film’s use of intertitles also isn’t quite to the standard you might expect; by the 1920s, intertitles were used quite frequently throughout a silent film to describe a scene or provide written dialogue. SCROOGE’s intertitles are essentially chapter headings, but they do provide a general sort of synopsis of the scene to come. Still, the intertitles were exhibitions of how film could tell a more complicated story without sound, a natural innovation that film relied on quite heavily as it evolved into a more complex and nuanced form.

The film itself is entertaining enough, for all of its three minutes or so. It’s one of Booth and Paul’s more muted films, although the film tricks you could expect from the pair come out with the introduction of Marley’s ghost. His quick appearance in place of the door knocker via a black hole portrait shot isn’t immediately impressive, but the drawing of the curtains later in the film to provide a black backdrop on which to create a double exposure effect is a neat blending of narrative and technical necessity. Otherwise, its staging looks fairly simplistic, even without comparing it to the obvious parallel of Georges Méliès and just looking at Booth’s other work. Unfortunately, the movie just doesn’t provide enough of a visual spectacle, which I’ve come to expect from Booth, to make up for the basic rendition of the plot.

Nevertheless, SCROOGE, OR, MARLEY’S GHOST was (and is) an entertaining novelty, a perfect trivia film for its notable firsts and a great early example of how a film can be changed and interpreted entirely differently by its cut and the status of its preservation. It belonged to the grand early tradition of film adaptations, and considering the limitations of the time, it did so with relative effectiveness. Oh, and if you need another little “fun fact” about the film: it was shown to King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra the same year Edward’s mother, Queen Victoria, died and he became king. Hopefully, the full, surely heartwarming cut helped out with the mourning and stresses of being a newly crowned king.

Make sure to catch up on and keep up with all of my essays on my favorite films here.